Guest post by Brian Fulghum.

Guest post by Brian Fulghum.

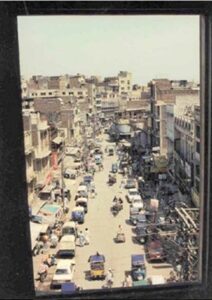

“Culture eats strategy for lunch” is a well-known expression of the importance of your organization’s culture and aligning it with organizational vision and strategy. I stumbled upon the importance of this principle when I was part of the leadership team running a business process outsourcing (BPO) company in northwestern Pakistan. We wanted to run a successful international business and respect local culture and ran smack into several cultural dynamics that made cross-cultural friction inevitable. How could we introduce grace in corporate culture while the local norm was revenge?

An eye for an eye

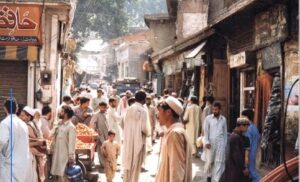

Revenge is a cultural value in Northwest Pakistan. “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” is the respected rule and expected norm. In fact, an old, old proverb immortalized as part of the Pashtun code of honor says that “A man is no Pashtun who doesn’t give a blow for a pinch”. A man who doesn’t respond in kind when his honor is besmirched loses it, and the way to get it back is to take revenge.

So there we were, wanting to respect local culture but not wanting revenge to be part of our corporate culture. I can see why revenge would be highly valued in the traditional, tribal society, but we knew it could be counterproductive to having the workplace environment we wanted for doing business internationally. Not only that, a heart of revenge can turn small unintentional mistakes into ongoing feuds that ruin the work environment for everyone. So we had to respond thoughtfully.

We didn’t launch an anti-revenge campaign as an effort against something we didn’t want, which could have seemed disrespectful to local culture. Change efforts against something negative are never quite as compelling or appealing as efforts for something good. So instead, we focused on what values we did want in our company to give us the results we wanted – a productive, harmonious workplace. As we chose our company core values, among the usual values like integrity, quality, and service, we also chose Grace. We defined Grace in the culture as “Giving the other guy the benefit of the doubt, even if we don’t think they deserve it,” because we’ve also been (or will be) in need of some grace.

Tough love

All company values need to be modeled from the top in order to be authentic, so as leaders we did our best to role model grace in the culture. Grace doesn’t mean we just blindly forgave everything and didn’t use disciplinary processes; rather it means that we had intentional, moderate, and “care-full” policies and processes that didn’t burn people, even when we had to let them go. Grace is also part of that concept we call “tough love” – practicing discipline not from anger but because it’s in peoples’ best interest.

With grace as a value we were careful to design our policies and procedures in a way that would not throw our staff under the bus in our pursuit of profit. As we worked toward operationalizing grace as a core value, when we chose and developed project managers and leaders, we instilled in them the watchwords: “We practice values-based management more than rules-based management.” When grace is part of the culture, both individual and group needs must be balanced. Disciplinary actions and even letting people go, when done with grace, are done to support those who perform well. Tolerating poor behavior is un-graceful for those who work hard. Once the concept of grace as a core value was seen in action a few times, our staff embraced the value.

With grace as a value we were careful to design our policies and procedures in a way that would not throw our staff under the bus in our pursuit of profit. As we worked toward operationalizing grace as a core value, when we chose and developed project managers and leaders, we instilled in them the watchwords: “We practice values-based management more than rules-based management.” When grace is part of the culture, both individual and group needs must be balanced. Disciplinary actions and even letting people go, when done with grace, are done to support those who perform well. Tolerating poor behavior is un-graceful for those who work hard. Once the concept of grace as a core value was seen in action a few times, our staff embraced the value.

When grace is part of the culture, both individual and group needs must be balanced. Disciplinary actions and even letting people go, when done with grace, are done to support those who perform well. Tolerating poor behavior is un-graceful for those who work hard. Once the concept of grace as a core value was seen in action a few times, our staff embraced the value.

Back up the values with fair processes

We asked our staff to show each other grace, and forgive each other when offenses occurred. And they did forgive most of the time. But because intended and unintended offenses just happen in workplaces, we needed to back up our values with fair processes for dispute resolution. Otherwise our value of grace would seem like so much worthless sentiment. So we were ready to mediate disputes between employees in ways that fit with cultural patterns of indirect communication.

Unintended offenses are things that happen in organizations – someone makes a remark or joke and someone else feels ridiculed and hurt; one employee outperforms another and gets rewarded, and the other feels jealous and vengeful. When these feelings are left to fester and escalate, ongoing feuds can turn from words to actions, especially when people feel that their honor is at stake. Whenever we became aware of these situations, we would talk to the employees involved privately to help them talk it out. Direct communication is valued in the west, but in the high-context culture of South Asia, people often use mediators as go-betweens to resolve misunderstandings. I needed to learn to play that part, reinforcing kindness to each party in each conversation. I was also able to educate employees about interpersonal and emotional intelligence topics that helped them understand one another better and to forgive.

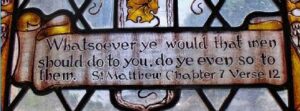

We had two women who just could not get along, gossiped judgmentally about one another and mistreated each other. I needed to mediate between them periodically to get them to agree to keep their interactions professional. I asked them to abide by the “golden rule” that is perhaps the most cross-cultural ethical framework, as it appears in some form or another in every major religion and culture. “Don’t do to someone else what you would not want to be done to you.” It is gracious to look past other people’s mistreatment of us without reacting in the same way, and instead to respond gently to safeguard a greater value.

Some project employees complained that daily work assignments were distributed unfairly and preferentially by the project manager. They were angry and the project supervisor was offended by the accusation that he was being unfair. I didn’t believe that project manager was acting unfairly, but didn’t want to ignore the workers’ feelings either because respecting diversity was another one of our core values. If I ignored the workers, I would foster grievances and allow perceptions of unfairness to fester. If I responded in a way that would undermine the project manager’s authority I would disempower a person we relied on. So we came up with a simple system to distribute daily work that the supervisor controlled but eliminated the possibility of him steering work preferentially.

Some project employees complained that daily work assignments were distributed unfairly and preferentially by the project manager. They were angry and the project supervisor was offended by the accusation that he was being unfair. I didn’t believe that project manager was acting unfairly, but didn’t want to ignore the workers’ feelings either because respecting diversity was another one of our core values. If I ignored the workers, I would foster grievances and allow perceptions of unfairness to fester. If I responded in a way that would undermine the project manager’s authority I would disempower a person we relied on. So we came up with a simple system to distribute daily work that the supervisor controlled but eliminated the possibility of him steering work preferentially.

In all my research about core values, I never found another for-profit company that used grace as a core value, but we did, and it worked. We all prospered for a variety of good business reasons that unquestionably included having a nurturing company culture made possible by our value on grace. Grace meant that our employees were proud of the company and more eager to see it succeed. Employees were more likely to settle disagreements amicably, and more likely to respond well when leadership needed to make difficult business decisions that had a hard impact. I will forever be a fan of strategically choosing company values to craft an effective culture. At our BPO in Pakistan, I don’t think that having a great business strategy would have helped us succeed if we hadn’t given due attention to our company culture.

Build inclusive cultures

On a more personal side, my leadership experiences in companies in South Asia have taught me that it IS possible to bridge cultures within an organization and develop an environment (organizational culture) that is welcoming overall. I’d like to say “welcoming to ALL” but I have encountered people from sub-cultures (extreme Taliban-minded sub-cultures, for example) that by their own ethnocentric nature would not allow themselves to be included in a diverse workplace. Their insistence upon dominating the conversation prevents them from hearing or accepting other views. I would also hesitate to say that there is any universal form of welcoming environment – any organizational culture that is welcoming and cross-cultural would have to be crafted according to nature and character of the sub-cultures it seeks to welcome. In the event the organization is to interact with a new culture, it might need to adapt its culture accordingly.

This wasn’t a foregone conclusion for me; it was a belief and hypothesis. We were attempting to do business in Pakistan without prior experience of it – we were adventurously entrepreneurial and making it up as we went along. I now have a basis of personal experience and success in crafting a unique organizational culture. I learned that I needed to adapt as a person, myself, to fit into the organizational culture I sought to create. For example, as a westerner, I prefer low-authority-distance, and I needed to learn to interact with workers more comfortable with high-authority-distance relationships.

A personal question that I ponder as a cross-cultural manager is the role that leaders and change agents play when working in other cultures. As a westerner, I am aware of a history and danger of “cultural imperialism” and want to avoid repeating it – yet at the same time believe that I have knowledge worth sharing. Managing across cultures inherently produces a certain tension between contrasting cultural values – who gets to choose which value becomes the norm in an organization? How do you demonstrate respect for local cultures when you are choosing to act in ways that act differently from them? It may seem odd to raise these questions after a piece about creating an organizational culture, but that’s the point – creating cultures that work involves wrestling with these questions. I believe that answers are discovered through inclusive dialogue, and work for that specific context.

My years in Pakistan and Afghanistan taught me to appreciate and enjoy Pashtun culture. It is a culture very different from where I grew up, and the differences are energizing. To me it’s fascinating, tribal, welcoming, and has an element of danger. Yet they have values I share that draw me as well, including friendship, hospitality, and a strong family orientation. Pashtun hospitality is lavish and warm-hearted, accompanied by great traditional food and music.

- Is my experience of having grace as a core value reproducible in other for-profit organizations?

- Is “grace” just another way to talk about kindness or forgiveness, or is it somehow different?

Brian Fulghum has more than 20 years of experience in cross-cultural management and communication, training, human resources. Brian serves clients as a sole-proprietor through Fulghum International Consulting. Brian’s passion is developing effective organizations, leaders and teams in multicultural and international contexts.

Marcella Bremer is an author and culture & change consultant. She co-founded this blog and ocai-online.com.