Guest post by David Hurst.

Guest post by David Hurst.

What if people were like plants and organizations were like gardens? Would managers and leaders realize that they can’t grow either people or organizations directly: that they can create only the conditions for growth? Would they begin to cultivate their organizations?

David Hurst gained many insights when he started to think more like an ecologist and less like an engineer. From maximizing performance at a moment in time, he shifted his focus to sustaining performance over time. In his highly recommended book “The New Ecology of Leadership” he shares a mental model that yields a better understanding of organizations and their developmental cycle. He shares his journey below.

“I had always felt that there was something missing from what I was taught in business school. Even today many academics regard management as a technical practice, akin to engineering. Some of them think of it as applied economics, bearing the same relationship to the dismal science as engineering does to physics! When I got out into the corporate world the gaps in my education became clearer. The most obvious of these was the ubiquity of power, power games and power struggles. This was a shock, as I had been educated in a rationalist culture, where everyone was meant to think in a logical, scientific way, and the facts spoke for themselves. In the power cultures I encountered, the “facts” were, within broad limits, whatever senior management wanted them to be and everyone spent a lot of time gaming the system. This was especially true of proposed mergers and acquisitions, where the numbers were particularly fanciful.

Then one day the firm I was working for, a medium-sized industrial distributor, was itself taken over in a wildly leveraged buy-out on the eve of a sharp recession. Almost overnight the enterprise went from being a growth-oriented, diversified public company to a cash-starved wreck. Interest rates in excess of 25% ravaged the balance sheet, just as demand for all our products and services collapsed. Fortunately, the firm owed the bank so much money that it was their problem too and they couldn’t afford to shut it down. Luckily our new owners had no management team of their own, so it was up to us, a small band of managers, to do what we could. But cash was king and, absent outright fraud, cash is only the number on a financial statement that you can’t fake. We had to get “real”.

Then one day the firm I was working for, a medium-sized industrial distributor, was itself taken over in a wildly leveraged buy-out on the eve of a sharp recession. Almost overnight the enterprise went from being a growth-oriented, diversified public company to a cash-starved wreck. Interest rates in excess of 25% ravaged the balance sheet, just as demand for all our products and services collapsed. Fortunately, the firm owed the bank so much money that it was their problem too and they couldn’t afford to shut it down. Luckily our new owners had no management team of their own, so it was up to us, a small band of managers, to do what we could. But cash was king and, absent outright fraud, cash is only the number on a financial statement that you can’t fake. We had to get “real”.

Getting “Real”

The next four years provided me with the finest management practicum that anyone could ever have, as the organization was forced to develop new relationships with all its stakeholders. Before the takeover management had focused almost exclusively on shareholders, while relying on a host of “management tools” – MBO, KPIs, performance reviews, incentive schemes etc. to keep our people “aligned”. I am not sure that these techniques had ever worked very well, but now they proved quite worthless, as our priorities changed drastically. Even the corporation’s elegant divisional structure, with its elaborate hierarchy, proved of marginal value as it faced a score of emergencies that didn’t fit into anyone’s job description. We were forced to flatten the organization and arrange ourselves into small egalitarian groups to tackle each of the issues. I called them “hunting” teams to contrast them with our previous “herding” structure.

We did our best to put flexible generalists on these teams and, apart from appointing a “sponge” on each (someone who can listen to what’s being said, see what’s being done and then squeeze it all onto one sheet of paper), we gave them all the information that we had, including everything stamped “Confidential” and sent them on their way with our blessing: “We’re relying on you” we said, “Tell us what we should be doing and we’ll do it.”

We did our best to put flexible generalists on these teams and, apart from appointing a “sponge” on each (someone who can listen to what’s being said, see what’s being done and then squeeze it all onto one sheet of paper), we gave them all the information that we had, including everything stamped “Confidential” and sent them on their way with our blessing: “We’re relying on you” we said, “Tell us what we should be doing and we’ll do it.”

We were astonished at the excitement and enthusiasm with which the organization responded to these changes. Lots of people ended up on either the teams or on sub-teams and everyone was steadily drawn into a new grand narrative. It told the story of a solid core business that had been saddled with too much debt and been hit hard by a recession. It would survive, however, if it could create and maintain the support of all its stakeholders: employees, customers, suppliers, creditors, unions, banks, communities, governments and investors. It wasn’t a story being imposed on people top-down; it was a story in the process of being written, a story to which everyone felt that they could contribute a line, a paragraph and even a chapter or two.

Four years later the firm came out of the mess with new owners and new bankers and a completely revitalized bunch of people. Helped greatly by a general economic recovery, the company went on to quintuple its revenues over the following four years, generating handsome returns for all the stakeholders.

Reflecting on Experience

As I tried to make sense of what had happened, I couldn’t find a suitable framework in my formal management education. Everything I had learned at business school seemed to capture only half of what had felt like a yin-yang experience. Up until then my knowledge of Taoist philosophy had come from pop psychology books, but now I set out to learn more. I ended up submitting a “Taoist” interpretation of our experience as an article to the Harvard Business Review. In it I suggested that there were two distinct logics continually operating in every organization. There was a hard, rational logic of tasks and a softer, intuitive logic of relationships. Instead of “yang” and “yin”, I called these polarities “boxes” and “bubbles”. I was delighted when HBR published the piece as their lead article in May 1984 (you can read it here: https://hbr.org/1984/05/of-boxes-bubbles-and-effective-management).

I have always read widely, but after the HBR article was published I started to devour books voraciously. I found that I could understand a whole lot of materials and concepts that I had not been able to grasp before. Philosophy, sociology, anthropology, economics, theology, political science, history, systems thinking: all these disciplines were suddenly accessible to me. The most fruitful of these fields was ecology. After all, Taoism is an early systems view of the world that makes extensive use of images drawn from nature. I have always been a metaphor freak and now I found that, by going back to the roots of these images, one could get a glimpse of the dynamics that had inspired them. I was introduced to the work of Canadian ecologist, C.S. “Buzz” Holling and his adaptive cycle, which shows how fire-dependent, temperate forests and other ecosystems go through regular cycles of birth, growth, destruction and renewal.

An Ecological Perspective on Organizations

It occurred to me that this cycle was analogous to the one that we had been through in our firm. It also seemed to match the trajectories of many other organizations and institutions. Once I had adjusted the forest analogy to handle people rather than just trees, all kinds of insights became available.

It occurred to me that this cycle was analogous to the one that we had been through in our firm. It also seemed to match the trajectories of many other organizations and institutions. Once I had adjusted the forest analogy to handle people rather than just trees, all kinds of insights became available.

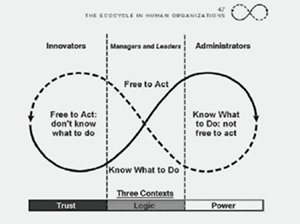

It seemed to me that enterprises are conceived in passion, born in communities of trust, grow through the application of reason and mature in structures of power. In the beginning, resources are “outside” and people have to operate in small, egalitarian groups to explore for these resources using “hunting” dynamics. Of course, many organizations fail at this stage, but the successful ones, who discover a recipe for success, start to grow prodigiously.

When they grow, they immerse themselves in strategy – rationality, logic, and calculation – as the recipe is spread far and wide. But, depending on the technology, the increasing scale imposes a growing cost. The division of labor and the resulting specialization, together with sheer size and the separation of people in space and time, lead to all kinds of problems. Moreover, as resources become centralized, members of the organization start to swivel inward to face the management hierarchy.

As the care of the bureaucracy starts to outweigh concerns for the customers, employees turn their backs to their clients. What was once an enabling bureaucracy can change into a byzantine, self-regarding political structure – a “herding” organization. The original purposes of the institution now play little role in decision-making; it’s all about “what” and “how”, with little concern with “who” or “why”. The means have run away with the ends. Stuck in a power trap, the organization is insensitive to a changing environment and unable to abandon the competencies that have got it to where it is. The stage is set for crisis and destruction, but with the possibility of renewal.

Ideally the “gardeners”, the stewards of this ecosystem, must be able to sense this situation long before the organizations slips into a power trap. They have to switch their priorities from a preoccupation with growth and scale and the suppression of “weeds” to a deep concern for innovation and system renewal. It may be time to break out the chain saw, to clear away the deadwood, to uproot and transplant, to make a bonfire of the debris and to plant anew. If the gardeners don’t do that, then eventually “nature” – competitors and external forces of all kinds – will do it for them, sweeping away old, decadent growth with flood and pestilence, wind and fire. The organization may be destroyed but its “ash” – the residue – will serve to fertilize open patches into which new growth can come, and the ecological cycle of birth, life, death and renewal will begin again…

A Different Mindset

I outlined this basic ecological model, with its “eco-cycle” counterpart to nature’s adaptive cycle in my first book, Crisis & Renewal: Meeting the Challenge of Organizational Change (Harvard Business School Press, 1995). Since then I have been using it to integrate huge swathes of management theory and practice, refining the model as I went. It all comes together in The New Ecology of Leadership, which presents a comprehensive mental model that I wish I had possessed at the outset of my management career.

I outlined this basic ecological model, with its “eco-cycle” counterpart to nature’s adaptive cycle in my first book, Crisis & Renewal: Meeting the Challenge of Organizational Change (Harvard Business School Press, 1995). Since then I have been using it to integrate huge swathes of management theory and practice, refining the model as I went. It all comes together in The New Ecology of Leadership, which presents a comprehensive mental model that I wish I had possessed at the outset of my management career.

This ecological model is fundamentally different from the current Anglo-Saxon model of management, which has its origins in the reforms of the American business schools conducted in the late 1950s. At that time, it was thought that management could become a social science along the lines of economics. The manager was viewed as a detached, knowing actor/agent in a knowable world, rationally calculating his options and issuing crisp, actionable instructions. Like an engineer, the manager was expected to analyze and diagnose situations and then to use context-free scientific principles to direct the organization where he wanted it to go. In this view, the manager was an agent for the shareholders, who wanted to maximize shareholder value and the employees of the organization were his instruments to achieve this. A Taoist philosopher would describe this perspective as “all yang and no yin”.

In contrast, from an ecological perspective, management is a practice, not an applied science. Managers can occasionally be detached observers but mostly they are immersed participants. The relevant universe of managers and organizations does not consist of matter, but of “what matters”. The facts never speak for themselves – they have to be selected and interpreted. This brings identity, ethics, purpose and power back into the picture. Management becomes a moral practice – not merely a technical one.

Living in the tension between the logic of tasks and the logic of relationships, people usually act their way in to better ways of thinking rather more readily than they think their way into better ways of acting. This makes for an effective practice because, when it comes to understanding cause-and-effect, every organization is unique. Techniques that work within one organization will not necessarily work in another, even when the two organizations appear to be superficially the same. Contexts matter, history matters and narrative matters.

Changing Frames of Mind

If people act their ways into better ways of thinking, then they don’t use logic and rational arguments to reach their positions – they use such arguments to justify positions already reached based on their experience. These experiences may not be first-hand for they include collective experience, like language, assumptions about human nature, and culture – anything that can frame and sustain a “habit of mind”. People think with frames before facts, so logic and data on their own are unlikely to alter their minds. To change a frame of mind, new experiences are needed. In The New Ecology of Leadership I suggest that there are three ways for managers to change an organization’s experience:

1. Change the collective experience of the organization by doing different things that are more relevant to the challenges expected. Sometimes (rarely?) an acquisition or merger may play this role, but the process is fraught with risk. A leadership development program geared to giving people the right kinds of experience might be another way of doing this. Used on its own, however, this is likely to be a slow process.

2. Senior managers must protect maverick employees who act and think differently inside the organization against the day when they will be needed. Alternatively, they must change managers outright and hire those who have been to the right “schools of experience.” The Positive Deviance (PD) movement can be seen as a community-based approach that fits here. In the case of PD, the mavericks are in the community and have developed adaptive responses to challenges faced by all. An experience is then designed that encourages the rest of the community to develop these adaptive habits.

3. Change the interpretation of the organization’s experience by remaking the stories told about it. Large, successful organizations often tell tightly-connected linear stories that imply that the firm is a money-machine, driven top-down by highly rational managers, implementing impeccably formulated strategies. These tales of seamless success may excite investors but they leave employees cold. What is needed is a story that will bring the organization’s story back to life – to create what philosopher Daniel Dennett calls a “narrative center of gravity” – by reinforcing the organization’s identity, its sense of “who we are” and “why we matter”. It is, in short, a narrative to which everyone can contribute.

These three approaches are not engineering tools but gardening implements; it’s all about changing the organizational environment. The goal is to cultivate the context and nurture the system, by recognizing that to everything there is a season and that some thrive only in some conditions and not in others. It’s not just about knowing what to do but about knowing the purpose – for who and why we are doing it – and when, where and how to do it.

Thus, from this ecological perspective, management is both a moral and technical practice. It is, as Henry Mintzberg has suggested, “an art, a craft, and a little bit of science” – just like gardening.

David Hurst is a speaker, writer, and management educator. He is a reflective practitioner with extensive experience, both as a senior manager and a teacher in several different countries. His website is https://www.davidkhurst.com/

This Post Has 2 Comments

Thanks for this excellent article.

This sort of thinking can be applied to all individuals and organisations by educating people in Integrative Thinking, Integrative Problem Solving and Integrative Improvement – Sustainable Development As If People and Their Physical, Social and Cultural Environments Mattered.

Marcella, and David; Bill LeGray Tweeted (in a @blegray reply), as follows: “Viewing/Studying/Working w Org Behaviors, w alternative mindful frameworks, may not mesh w historical viewing well, but can increase Yields!”

Obviously, I agree with David’s findings, and have developed similar thoughts after many years. Especially, beginning with a visitation to the Rain Forest, while residing in the NW. And, actually the head of the 1st OB Program was an Economics PhD w an undergrad degree in Biology.

Relative to OD Leadership and Change teachings, the ecology aspect was considered as those “human side organism/organic experiences which influenced human conditions associated with both animate and inanimate behaviors.