Guest post by Paul Gibbons.

Guest post by Paul Gibbons.

In March 1993, the derivatives market was booming and banks, although intoxicated by the profits, were worried about the risks of these strange, complex instruments and how to control the armies of traders making all the money. The normally reserved world of British commercial banks had been taken over by brash, loud-mouthed traders. Senior management loved the income, but did not understand the math, hated the new trading room culture of risk, aggression and vulgarity, and were at sea with how to manage a business they did not understand. So they called in the cavalry: consultants.

“Caminante, no hay camino. Se hace camino al andar.” (Traveler there are no paths. Paths are made by walking. From “The Science of Successful Organizational Change”)

How to set fire to 3 million dollars

PwC had assembled a team of rocket scientists from MIT, from Harvard, and from Oxford to help Barclays develop a comprehensive “Risk Management Framework”. I was on the team as “a math guy” and because (as a former trader) I spoke the traders’ language, the gammas, deltas, and the epithets.

We toiled for months interviewing senior leaders, traders, other risk experts, and writing our reports by midnight oil. We wrote twelve volumes of several hundred pages each. All volumes were detailed and dense, suggesting what strategy, systems, accounting procedures, processes, and management practices Barclays should use to manage risk.

We charged 1.8 million pounds ($2.7 million). And then nothing happened.

“What?” you say, “surely not nothing?” To be more precise, our findings were presented to the Board who nodded vigorously at all the right times. Then we presented to the Executive Committee, to the Managing Directors, to the Business Unit Heads, and to their teams. They all nodded and applauded. No PowerPoint slide was left unturned.

“What?” you say, “surely not nothing?” To be more precise, our findings were presented to the Board who nodded vigorously at all the right times. Then we presented to the Executive Committee, to the Managing Directors, to the Business Unit Heads, and to their teams. They all nodded and applauded. No PowerPoint slide was left unturned.

From Master of Universe Consultant, to snake-oil peddler on my first project. What went wrong? Although they found our logic compelling, and our recommendations sound, Barclays failed to “Mind the Gap”: the one between agreeing with something and doing it. Barclays might as well have lit a bonfire in Lombard Street with the three million bucks.

How could our recommendations not have been implemented when they were so worshipful of them? If our recommendations were as good as we and the bankers thought, what else should we have done to get them adopted? When were they going to blow the whistle on consultants for charging huge fees, producing no results, and hopping off to the next assignment?

Reports in drawers and personal change

Little did I know that such “epic fails” were more the rule than the exception in consulting; they have a name, “the report in a drawer.” Over the next 18 months, I worked on several strategy projects that soon decorated executive shelves and bottom drawers.

This professional “epic fail” paralleled one in my personal life. In 1980, still a teenager, I worked in cancer research before starting medical education. My research project was to study the biochemistry of cancer by treating little white mice with a carcinogen from cigarette smoke. Despite this, and since the age of fourteen, I smoked a pack of Marlboro Red per day. At the lab, I would squirt the cigarette extract, watch the mice get cancer, and grab a quick smoke between experiments. While working at Barclays, I still frequented the parking lot for smoke breaks, so for almost twenty years I had ignored all the science, some of which I produced first hand, which told me I was killing myself one cancer stick at a time.

I would watch the mice get cancer, and grab a quick smoke between experiments. The link between the failed project at Barclays and my death wish was not lost on me. There must be a link between how I systematically defied in-your-face rationality, and how Barclays ignored our advice on Risk Management.

This birthed a tremendous hunger: how do people change, and how do businesses make real change happen? How do good ideas get acted upon in the real world, and how do reports find their way from bottom drawers into hearts and minds[Field]? This seemed to be a problem at the root of human happiness, business prosperity and how we manage ourselves as a society.

The equation seemed to be: E times X = Change

E seemed to be expertise, knowledge, research, statistics, advice, reasons, rationality, and clear thinking. My strategy colleagues and I were good at all that.

X was the bit that stumped me completely, that I knew nothing about – the “special sauce” that combined with reasons produced change. X had eluded me in my personal life, and now in my professional life. I wanted to make a difference, not just espouse grand theories, and to be someone who did not just talk a good game but could play ball. I wanted X.

I changed gears. For almost two decades, I lived, ate, and breathed organizational change. My immersion was obsessive: in its academic disciplines (Psychology, Sociology, Organization Development, and Organizational Behavior), training in Daryl Conner’s change toolkit, Californian “self-actualization” workshops, training as a counselor, working as a change manager in dozens of businesses, and teaching the advanced change management program to management consulting partners.

From the laboratory to the sweat lodge

Little did I know that leaving the solid bedrock of science for the world of change meant journeying to the opposite end of the spectrum – a world where ideas were much harder to test.

At first, I accepted books such as Gladwell’s The Tipping Point, or Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence uncritically, never wondering how much meat there was on the sandwich. My new change colleagues and I talked about emotions, socially constructed realities, presencing, living systems metaphors, ancient wisdom, consciousness, cultural memes, spiritual values, and stakeholder engagement. I loved the writings of 1990’s change gurus, e.g. John Kotter (Harvard), Tom Peters (McKinsey), and accepted their ideas because of their reputations.

Then, as I traveled farther down the change rabbit hole, I encountered writings by change gurus that would say: “a leader learns to cultivate her power as the result of being tuned into her inner voice and guided by intuition”, “leadership is a right-brained phenomenon”, and “working with people’s feelings is the essence of quantum leadership.” One workshop attended by very senior business people used a labyrinth to evoke insight and creativity. The premise was that if one walked around this ancient sacred structure with a question in mind, insight and creativity would emerge. I just got dizzy.

I was now a stranger in a strange land. I knew there was more to producing actual change than reason yet change theories had almost no science to back them up, and most of my fellow practitioners disdained science in favor of “other ways of knowing”. I spent a decade in the “integral” community, and from 1995 earnestly studied the writings of philosopher Ken Wilber who, I believed then, had an epistemological framework for integrating science and spirituality. I was one of the first to use his theories in writing on business and leadership, and became active on the “integral” speaking circuit at dozens of workshops and conferences.

Here, too, I became disenchanted. I found most of my fellow learners on the integral journey effectively embraced pre-scientific thinking (superstition, supernaturalism, New Age), yet believed they had “transcended and included” science.

Pre-science, or anti-science thinking does not, by any means, just apply to the spiritually inclined change practitioner; even hard-nosed business people do not worry about evidence. During my 30 plus years in business, and 20 plus years dispensing consulting advice, no client ever asked me whether there was evidence to support the models, frameworks, tools, methods and ideas I proposed using. Never. I worry about using methods on billion dollar projects that are based on beliefs based on skimpy evidence. How do we evaluate methods in this science-free world?

The change world (Organization Development, leadership development, and change management) seemed to comprise of great “people-people” that made for outstanding facilitators, but I had doubts about how reliable methodologies guided by those underlying belief systems might be.

Yet, how much better proven were the more conventional tools I favored, such as business cases, organization performance models, risk registers, stakeholder analysis and criterion matrices? Was it just a matter of taste? While I disdained some of the more esoteric approaches, I had equally little evidence to prove what I did.

More accountability, more evidence

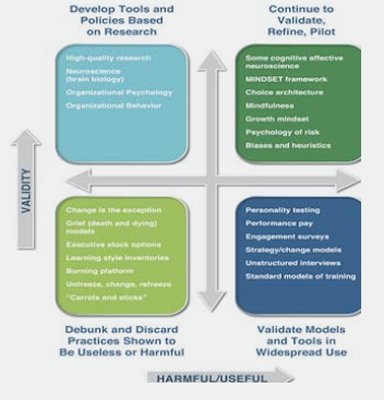

Figure 1 divides the change world into valid/ not-valid and useful/harmful. I believe that the future lies in moving as much to the upper right box as we can – that is, using practices that are both valid, and useful. This will require a shift in business culture toward more scientific validity, more measurement, and greater accountability for results. The shift will take decades, but there are indications that it is already underway with new “analytics” and data-driven approaches to decision making, and a phenomenon called evidence-based management.

There is much research (top-left) that is little known or used; businesses must move practices (policies, models) from the bottom-right box into the top-right by evaluating, proving, and testing them; policies models and practices that are proven harmful should be moved to the bottom-left and discarded. This sounds true, I hope. But consider the training world. Evaluation forms after training sessions are uncorrelated with transfer of skills to the job. They measure popularity. Yet there are few serious attempts to measure the results of training more rigorously. Can the armies of people teaching (say) emotional intelligence today prove a) that participants are sustainably more emotionally intelligent (say one year hence), and b) that this materially affects workplace outcomes (engagement, productivity, etc.)?

The war between validity and usefulness

In the business world (especially in HR/ change), we have a war between the “validity people” and the “usefulness people”. The validity people berate the usefulness people for lack of evidence and pseudoscience. The usefulness people (when they do not just ignore the researchers) respond, “Leave me alone, I have a job to do.” The usefulness people, in their desire to get on with things, are guilty of dropping rigorous evidential standards, hence we gets fads, and lack of accountability. They then berate the validity people for not “being in the real world.” This theory-practice war destroys value.

Many of the hot areas in the human sciences are contested. Neuroimaging is exciting, but there is much debate around whether brain scans show what they claim to show. (One researcher put a dead fish in a brain scanner and found it lit up when shown images. This did not end the debate about imaging!) Yet most people in the world of “neuro-leadership” are unfamiliar with this huge controversy and are uncritical of whether it is useful.

On a more traditional topic, there are volumes written about performance-related pay (PRP), stock options, and other incentive schemes. Over 90% of the Fortune 500 (US) has such schemes – yet the evidence is at best mixed, and at worst contradictory. Furthermore, such schemes can promote excessive risk-taking which helped plunge the world into recession in 2008.

The list goes on: right-brained leadership (no such thing), learning styles (no link to learning speed, or retention), brain training (no transfer to real life problem solving), “denial-anger-bargaining-depression-acceptance” (not true in the dying, not applicable to organizational change).

The list goes on: right-brained leadership (no such thing), learning styles (no link to learning speed, or retention), brain training (no transfer to real life problem solving), “denial-anger-bargaining-depression-acceptance” (not true in the dying, not applicable to organizational change).

On these contested topics, it matters less whether I am right or wrong on a particular topic than that we start to ask ourselves the hard questions within the practitioner community (change, HR, OD, leadership people). There is much virtue in “being positive”, “appreciative enquiry”, and “staying constructive”, but in this practitioner’s view this has become an absence of critique.

The skeptical mind

Scientific evidence is not necessary for everything: agriculture existed in pre-literate societies as practices developed by trial-and-error were handed down over generations. However, they also made mistakes and some rituals they thought worked (such as those to influence the weather gods) were wasteful. Business is more like that than it is like medicine, but even medicine was based on folklore 200 years ago. Doctors believed in things like “humours” and used leeches. As with business change today, patients sometimes got better and sometimes died. When they improved, the doctors took the credit. When change fails, do we admit to ourselves that some of our “rain dances” may not work as well as we think?

The study of cognitive biases has shown that we are capable of enormous self-deception. 96% of people think they are above-average listeners. People have mystical faith in their gut (intuition), yet research shows that “I just felt X would happen…” is no more accurate than a coin flip. The optimism biases mean (usually) that when we evaluate our results as coaches and consultants, the data we perceive are skewed toward the positive (the so-called confirmation bias). Where does this leave us?

The re-enlightenment

In the history of ideas, the Enlightenment promised “to make the world a better place through the use of reason”. This overturned political structures, introduced the treasonous notions of equality and democracy, and (with the Scientific Revolution) ushered in the modern world. However, change in the world of ideologies takes centuries, and my contention is that the Enlightenment (rather than ending around 1800) has only just begun.

In the history of ideas, the Enlightenment promised “to make the world a better place through the use of reason”. This overturned political structures, introduced the treasonous notions of equality and democracy, and (with the Scientific Revolution) ushered in the modern world. However, change in the world of ideologies takes centuries, and my contention is that the Enlightenment (rather than ending around 1800) has only just begun.

Why? The revolutions of the 18th century ostensibly brought democracy and egalitarian thinking to the world. This is far from true. Women and people of color had to wait one or two centuries for “their turn”. As one historian said, the American Revolution was revolutionary only if you were white, owned land, and were male. Today we still struggle with extension of equal rights in the areas of gender, and sexual orientation. The war against oppression and inequality was not won in the 18th century and is far from won today.

The same is true with science and reason. While scientific ideas and methodologies began to change practices in some areas, other areas remain untouched by them. Medicine was no different than witchcraft until the late 19th century. Evidence-based medicine (basing medical practice on what research demonstrates to be best practice) only became popular in 1998. Until then, doctors based what they did on what they were good at, medical custom, what their colleagues did, what they learned at medical school and other historical custom.

The same is true with science and reason. While scientific ideas and methodologies began to change practices in some areas, other areas remain untouched by them. Medicine was no different than witchcraft until the late 19th century. Evidence-based medicine (basing medical practice on what research demonstrates to be best practice) only became popular in 1998. Until then, doctors based what they did on what they were good at, medical custom, what their colleagues did, what they learned at medical school and other historical custom.

Psychology, and business psychology, are where medicine was 150 years ago. We discover more every decade, but each decade also sees the reversal of many ideas taken for Truth. Until 60 years ago, behaviorist psychology was the dominant paradigm. Then the cognitivist revolution (just waning now) began to use computer and information sciences as their metaphor for the mind. Now neuroscience (the ultimate in reductionism) tries to link biology, mind, and behavior.

The essential question is: in which areas should we trust science, and in which should we disregard it? Most of humanity still chooses their science according to their belief systems. People from the political right dispute climate science, many people on the left dispute the science that supports vaccination. The latter means that measles and polio, after being eradicated, are making comebacks. The former, rejection of climate science, may make disease epidemics the least of our worries.

We still wrestle with these issues: science versus faith; reason versus intuition, belief versus evidence. For the leadership/change practitioner this means, in my view that we must have:

- A healthy skepticism about ideas from popular psychology and their validity;

- Caution when trusting sexy-looking science (such as brain scans);

- A willingness to challenge experts and gurus (e.g. Gladwell, Drucker);

- A commitment to holding ourselves to the highest standards of accountability (including an awareness that our view of our own effectiveness is highly skewed toward the positive);

- The discipline to using the highest standards of evidence available to inform our practice.

What do you think..? Do you agree?

Paul Gibbons is the author of The Science of Successful Organizational Change: How Leaders Set Strategy, Change Behavior, and Create Agile Cultures.

This Post Has 4 Comments

Thanks immensely Marcella for all your support – have a wonderful 2016!

Thank you, Paul! Let’s make this year wonderful… and let’s keep learning about change processes! Thanks for sharing your article.

Paul. I have been working on change in Central and Eastern Europe for well over a decade. I realised the day I started in 1998 that the “report” idea would never work. The first planning office I went into in Estonia already had a cupboard full lying there gathering dust. Since then my success and that of my colleagues has gone up and down. We have looked hard at the academic research and tried to use the latest knowledge, but we found that some concepts like Kotter were alien to the societies in which we wanted to bring change. How can you deliver vision if you never talk to subordinates as a rule because it would dissipate power. We keep looking for better.

The main thing we have learned is that change is a very political act and that it has no value if the leadership are not fully behind it. The leaders must be willing to “move the money” or great hopes simply fade away. The second thing is that change is an extremely intimate process for each person. Most workers within the organisation at all levels need to be given new skills and confidence to use them. The higher the power distance of the company or organisation, the greater is the challenge in doing this – witness the very visible failures in Ukraine. The key is to sit alongside the person who must make change at any level and help them do their day to day work in a different way. You can only hope that this sticks and becomes a new habit and set of beliefs. It will if encouraged – but it is not always. Sometimes new ideas are simply punished and the change rapidly stops This transfer of concepts and skills can be at the level of Mayor and Minister in government, or the lowly person moving forms around in the accounting department. This method takes political know how, time, knowledge, patience, and understanding on the part of the consultancy team. It demands the ability to create trust everywhere you work – and this is not at all easy in some environments. It can easily take 10 or more years in the Former Soviet Union. Given the aforementioned political support, this method works, but it is seriously slow.

Sounds as if you have tremendous on-the-ground experience in a fascinating environment.